| Name ▲▼ | Origin ▲▼ | Description ▲▼ |

|---|---|---|

| God name "Annammr i" | Hindu / Puranic | Form of the god V IS'NU. The patron deity of kitchens and food. A shrine at Srirangam in southern India contains two-armed bronze images of the god. Attributes: a ball of rice in one hand, and in the other a container of payasa (sweetened milk and rice).... |

| God name "Daikokr" | Shinto / Japan | God of luck. One of seven gods of fortune in Shintoism and often linked with the god EBISU. Originally a god of kitchens, he became a deity concerned with happiness. He is depicted as a fat, well-to-do figure seated on two rice bales and carrying a sack on his back. He also holds a hammer in his right hand. In depictions there is often a mouse nibbling at one of the rice bales. Small gold icons of the god may be carried as talismans of wealth. According to tradition, when Daikoku's hammer is shaken, money falls out in great profusion. In western Japan he is also syncretized with the god of rice paddies, TA-NO-KAMI, and thus becomes the god of Agriculture and farmers. He may have developed from the Buddhist god MAHAKALA.... |

| God name "Kamado No Kami" | Japan | God of kitchen stoves Japan / Shinto |

| God name "Oki-Tsu-Hiko-No-Kami" | Japan | A child of the harvest god and the god of kitchens. Japan |

| God name "Oki-Tsu-Hiko-No-Kami" | Shinto / Japan | God of kitchens. One of the offspring of O-Toshi-No-Kami, the god of harvests. The consort of Oki-Tsu-Hime-No-Kami and responsible for the caldron in which water is boiled.... |

| Goddess name "Oki-Tsu-Hime-No-Kami" | Shinto / Japan | The goddess of kitchens |

| God name "Tsao Chun" | China | God of kitchens and stoves who ascends to heaven every year to report to the Jade Emperor on the good or bad behavior of each family member. China |

| God name "Zaoshen" | China | A god of kitchens |

| God name "Zaoshen aka Zaojun" | China | God of kitchens. China |

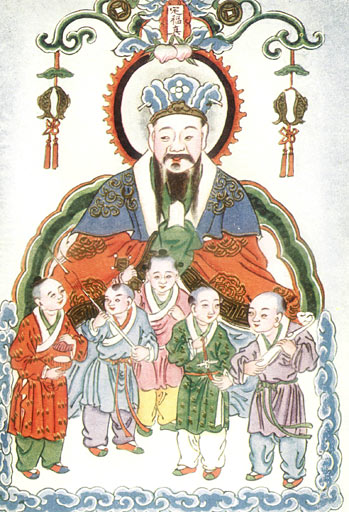

Legends About the Kitchen God

There are many legends about offering sacrifices to the Kitchen God. In the old society before the Spring Festival, each household prayed to the Kitch- en God, hoping that he would "put in a good word for the whole family when in the heavens and bless them when on earth." They thought the whole household would then live peacefully in the coming new year. Many people got along cautiously and behaved themselves well in order to make the Kitchen God bring them blessings. As time went by, it was discovered that poor people, respecting the Kitchen God piously, never got rewarded; while the rich people's lives got better and better only because of their good offerings. Then the commoners be- lieved that the Kitchen Lord surely liked to hear good words and receive bribes just like officialdom in the human world. Later people added a kind of malt sugar shaped like a melon in their offerings to the Kitchen God in the hope of sticking up the god's teeth and keeping his mouth shut when he went back to Heaven.

The custom of sacrifices differed in various places. Some places held two sacrifices: one on the evening of the twenty-third day of the twelfth lunar month, with offerings including chicken, duck, fish, meat dishes and wine; the other on the next evening with fruit, peanuts, melon seeds, day lily and cakes. Malt sugar was a must in any sacrifices. The first sacrifice was meant to bribe the Kitchen God, holy- hag that he would not bring trouble to the worship- pers. Purpose of the second sacrifice was to make the god clear-headed after the first evening's good food and wine; thus he would not talk irresponsibly in Heaven.

Offering sacrifices to the Kitchen God was unique in the national minority areas. The Zhuangs in Guangxi made four sacrifices from the first to the fifteenth day of the first lunar month. They prayed for protection from eye disease and scabies. These were called "Kitchen King Sacrifices," and were divided into grand and minor sacrifices. The form- er's offerings included a piglet and a rooster and a sorcerer would be invited to take part in the grand sacrifice; the minor sacrifice had only half a kilo of pork and a rooster as the offering and no sorcerer was to take part. Women had to go away from home on both sacrifices, otherwise, the legend says, the Kitchen God would not dare come out to take offerings.

The Truth About the Kitchen God

The origin of worshipping the Kitchen God was rather complicated but time-honoured. As it was regarded to be closely related with people's food, drink and daily life just like land, wells, houses and roads, it naturally became a matter of worship. Sacrifice to the Kitchen God was listed as one of the state sacrificial ceremonies in The Book of Rites which collected records about etiquette and cus- toms before the Qin Dynasty.

Who is the Kitchen God? Many legends about it can be found in Chinese history. Some say it was a man; some say a woman. The same is true of his family names. But Zhang might be his family name.

Why did people fabricate a Kitchen God? The fact is that people of primitive society wanted to show their gratitude to the inventor of fire so they held a special sacrifice to him every summer. It was said that summer symbolized fire and so did the kitchen. Legends about the Kitchen God can be traced to the Yin (Shang) Dynasty (c. 16th-llth century B.C.), when the diety was represented as an old lady responsible for food and drinks. Some ancient books describe the Kitchen God as "a beautiful young woman in red." Some books say, "There are red-shell worms the size of a cicada on the kitchen ranges, which are popularly called roach or zao ma (kitchen range horse)." In Sichuan Province, the roach is called "oil-stealing granny." Ancient people regarded it as a divine being. This, probably, is the origin of the Kitchen God.

After the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220), the Kitchen God became a male deity. Sacrifice to him was then just a commemoration with little supersti- tious colour. The formation of a class society had injected new content into it, and legends about the Kitchen God were closely associated with money- making. One legend said that, during the reign of the I-Ian Dynasty's Emperor Xiandi (91-49 B.C.), the Kitchen God suddenly appeared in the morning on the eighth day of the twelfth month when a man called Yin Yufang started cooking his meal. The man had a yellow sheep, which he slaughtered and offered as a sacrifice to the Kitchen God. From then on he had good luck at every turn and quickly became rich. He built himself a big, elaborate house and bought five thousand hectares of land. His family members lived lives of luxury, dressed in silk ate nice food, and were waited upon by servants at home and travelled by carriage and riding on hors- es. His two grandsons both became high-ranking officials. The story about the Yins caught people's attention, especially those who yearned for wealth and position, touching off a craze for offering sac- rifices to the Kitchen God.

In the meantime, many tales circulated about the Kitchen God. One said that at the end of every month the Kitchen God would ascend to Heaven to inform the Jade Emperor of the crimes committed by so-and-so on earth (see Huai Nan Bi Wan Shu, or The Ten Thousand Infallible Arts of the Prince of Huainan). Another said the Kitchen God and his wife were named so-and-so and they had six daughters. As time went on, the Kitchen God be- came empowered not only to take charge of a family's food and drink but also to control life and death, fortune and misfortune. He kept a regular register of one's good and bad deeds and reported them to the Jade Emperor once a year.

In order to preserve the feudal system and put the people at their beck and call, the feudal rulers concocted many stories about the Kitchen God being the arbiter of people's destiny. According to Bao Pu Zi (The Book of Master Baopu), when the Kitchen God reported people's crimes to him, the Jade Emperor would punish the criminals by reduc- ing their life span by three hundred to three days as he saw fir. In other words, if one wished to live long, one would have to behave according to the ethical codes of the time. In fact, people who believed in the existence of deities would never dare to offend the Kitchen God and always held him in esteem in the hope that he would put in a good word for them when in the heavens and bless them when on earth. Each month on the first and the fifteenth, people had to make offerings to him, and on the day whan the Kitchen God was said to be going back to Heaven for consultations, the offerings would have to be extravagant, including fish, meat, wine and sugar. Thus, the more bribes one gave the Kitchen God, the more good words the latter .would alleged- ly put in for him. It was believed that those who could not afford such offerings would always be in for trouble. These legends, of course, represent only the wishes and yearnings of the people.

The legends about the Kitchen God are contra- dictory because ancient people could not explain many things in the natural world and therefore believed everything was controlled by some divine beings in the unseen world. The fact that the Kitch- en God turned from female to male indicated that human society had developed from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society. As times changed, people's imaghaation also changed and so did the deities concocted by them out of thin air.

The Kitchen God became more and more pow- erful and ascended to Heaven frequently to report on people in the mundane worM. The ruler used the deities to frighten the people and bind them to his will.